Margôt Maddison-MacFadyen writes this Research Profile at the conclusion of the Empire, Trees, and Climate Project. Therefore, her responses are about events that actually happened as a team member, 2014-2017. She is the Canada Research Chair Postdoctoral Research Fellow for Global Environmental Histories and Geographies situated at Nipissing University, Ontario. Dr. Kirsten Greer is her mentor.

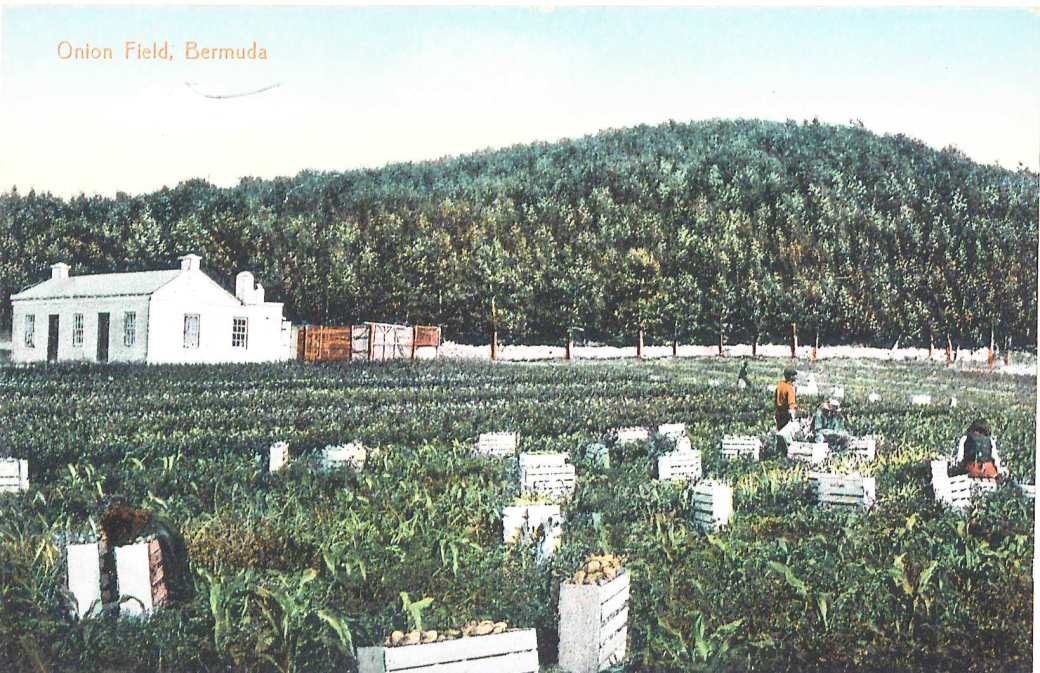

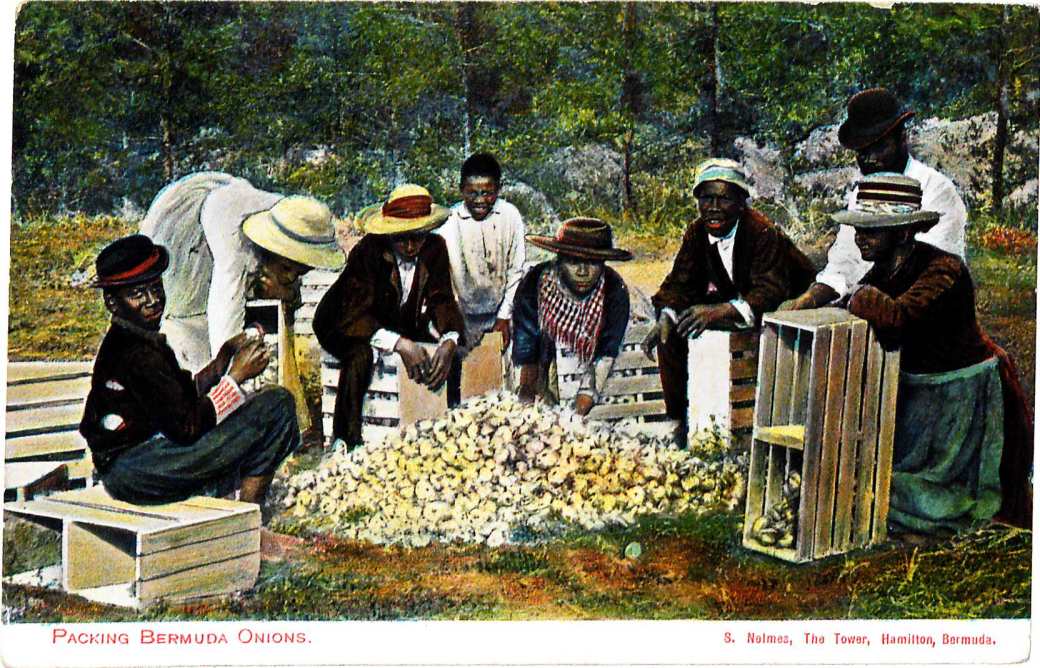

Q: What is your specialization?

That’s quite the question to ask a recent graduate of an Interdisciplinary PhD program! Mine, completed in May 2017 at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, includes two faculties (Humanities & Social Sciences, and Education) and four subjects (Education, Gender Studies, History, and English Literature). However, the history of enslavement in the maritime Atlantic (The Middle Passage, colonial enslavement, slave rebellion, Abolition, and Emancipation) is a key specialization of mine.

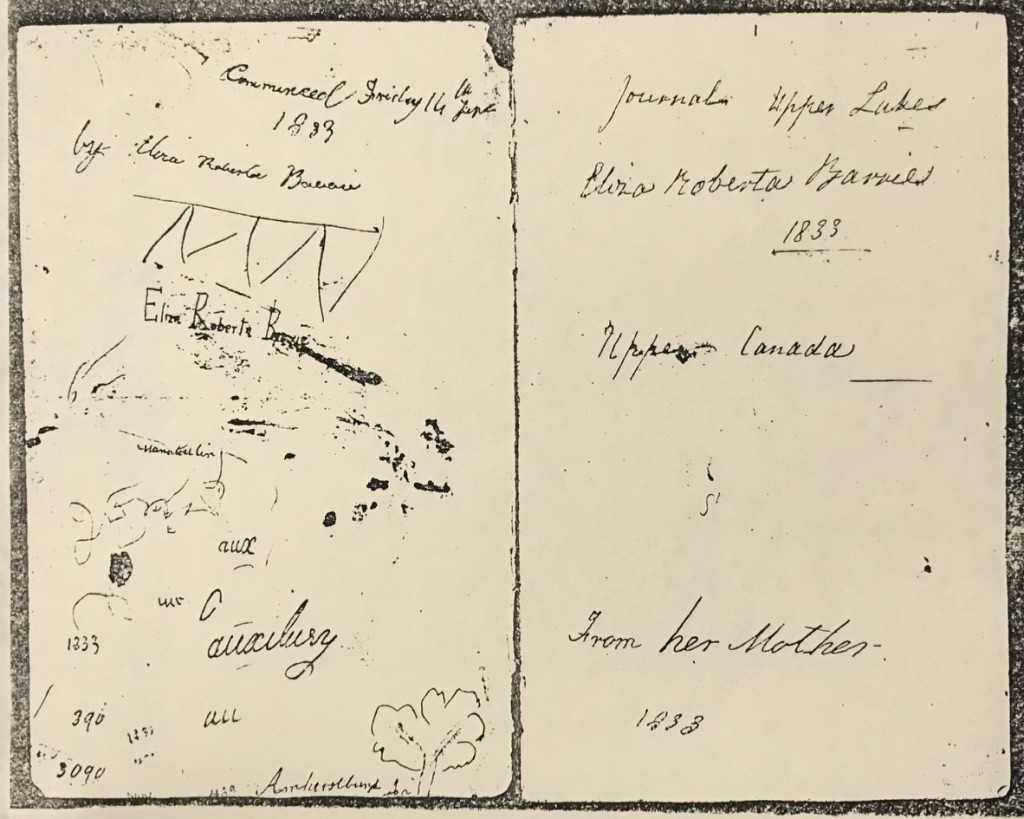

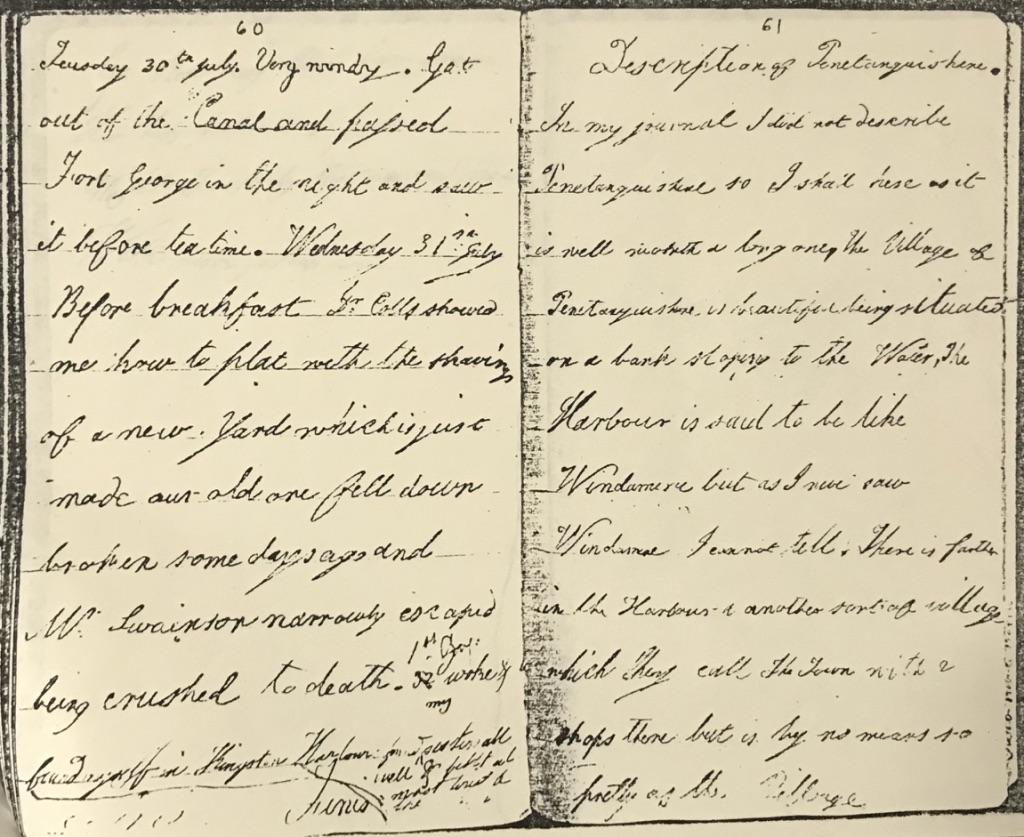

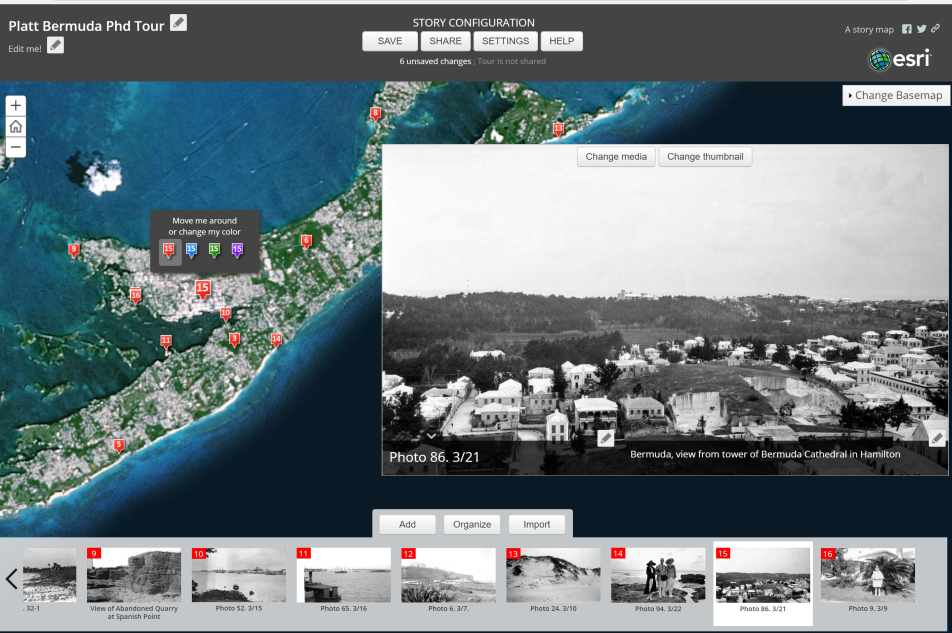

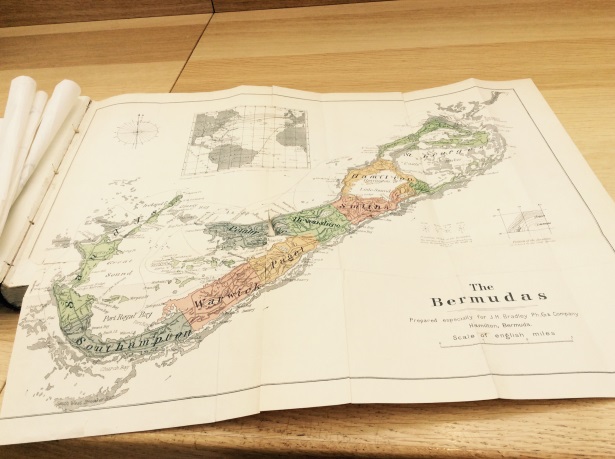

Mary Prince as an historical subject is a second specialization. Bermuda-born, Prince (1787/1788 – after 1833) is the first known black woman to have her story of enslavement and freedom written down and published. Her testimony, or slave narrative, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself was first published in 1831. My work as a PhD student was partially to visit every territory in which Prince had lived (Bermuda, Grand Turk Island, Antigua, and London [UK]) and to confirm her testimony through primary sources and by visiting sites of enslavement associated with her and her parents. Mary Prince became a Bermudian National Hero in 2012. Please see my website maryprince.org where I have placed some of my findings, including historical photographs and images of documents gleaned from archives.

A third specialization is the Pedagogy of Remembrance. I have theorized an educational approach to open students’ critical historical consciousness in regard to histories of mass violence, such as The Holocaust, The Middle Passage, and the genocide of North American Indigenous Peoples. My approach, based on the work of others (see the bibliography following for titles authored or edited by Roger Simon, Peter Seixas, and Tom Morton), has five interrelated components and is keyed to autobiographical survivor accounts, such as slave narratives in the case of The Middle Passage and colonial enslavement.

Q: Why were you interested in the project?

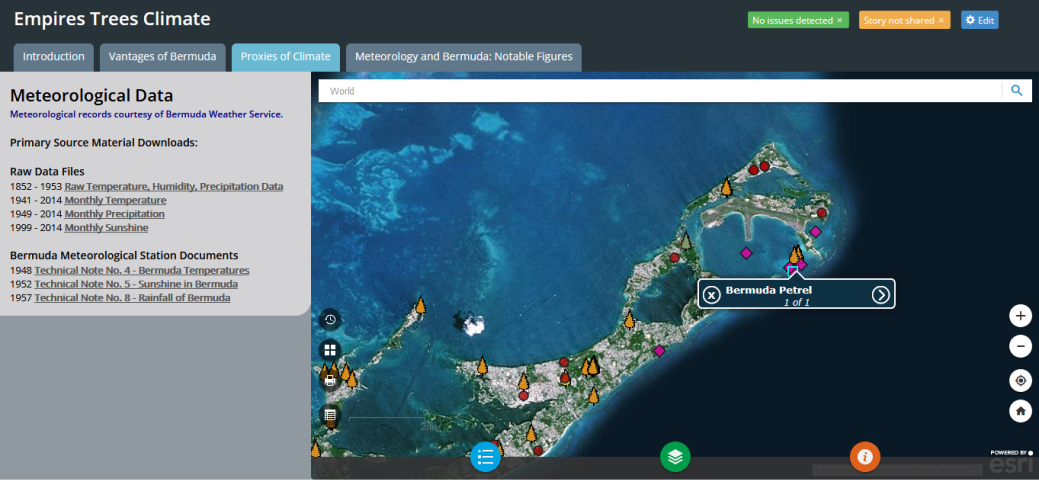

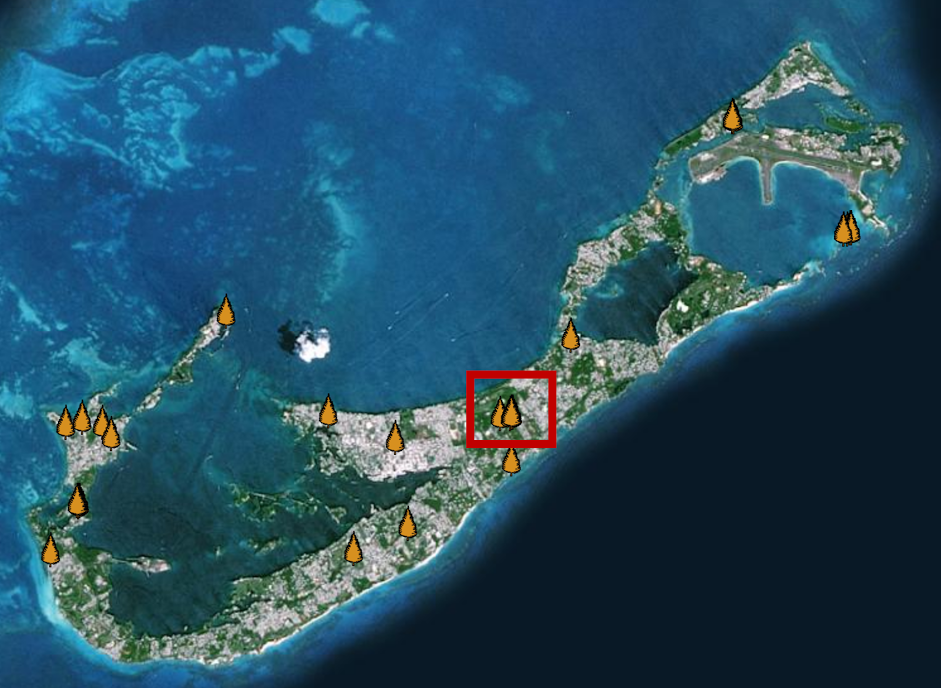

A focus of Empire, Trees, and Climate is Bermuda, the territory of Mary Prince’s birth, so, for me, any opportunity to visit Bermuda, the Bermuda Archives, and the National Museum of Bermuda was not to be missed.

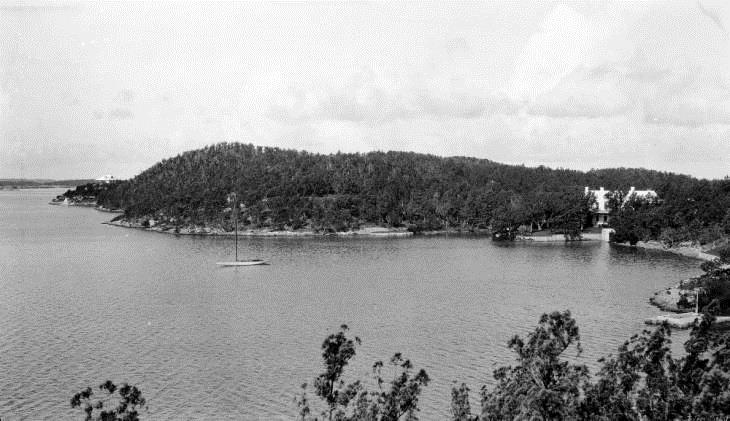

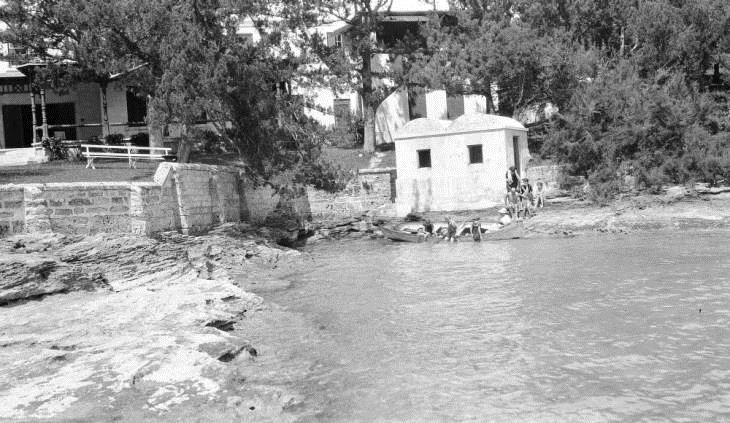

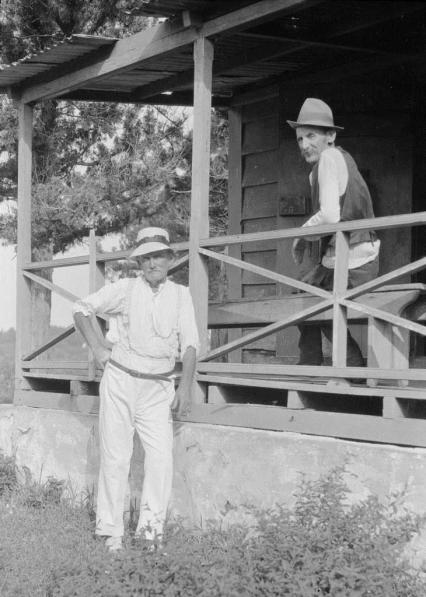

But there was also Cavendish Hall. One outcome of my PhD project was that I located two more structures associated with Prince in Bermuda, for a total now of five. One of the two structures I was able to locate, Devonshire Parish’s Cavendish Hall, was possibly built as early as the late 1600s. From its beginning, Cavendish was a home of the Darrell family. Although Cavendish was turned into condo units in 1969 and is almost unrecognizable from historical photographs, sections of the old building remain.

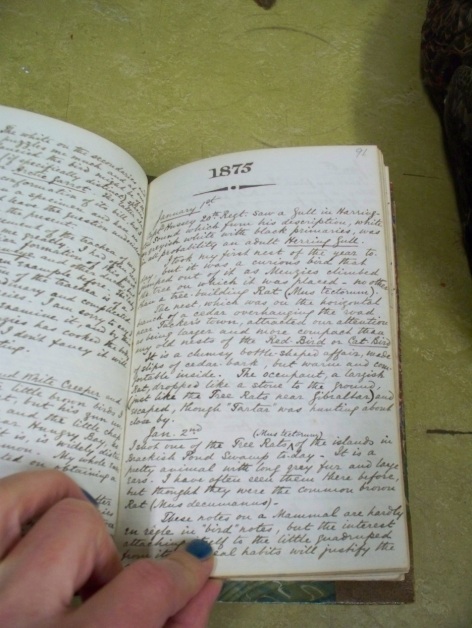

A primary source, “The Journal of John Harvey Darrell” compiled by his daughter Harriet Darrell long after his death, but written in the nineteenth century, informs readers that Cavendish was originally built entirely of Bermuda cedar. This means still-standing Bermuda cedar posts in the cellar may be well over 300 years old.

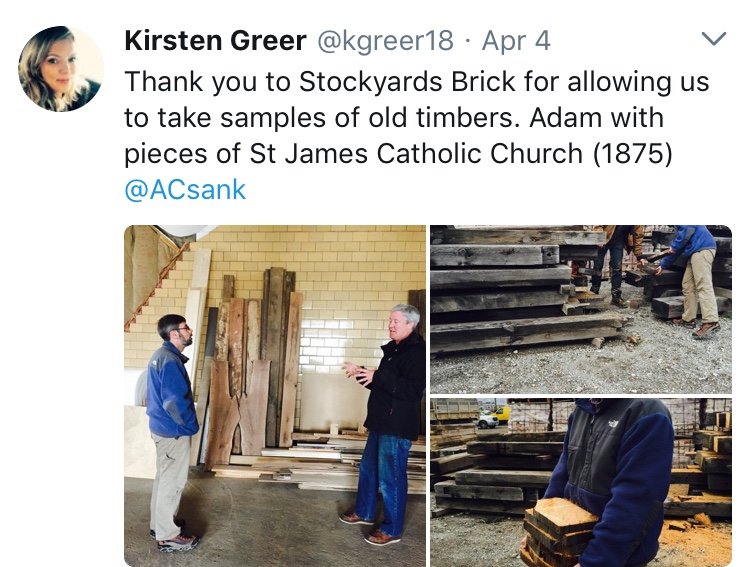

I was interested to find out more about the old home, and I did. Team member and dendrochronologist Adam Csank was able to visit Cavendish with me, and we gathered timber samples from Bermuda cedar posts in the cellar, as well as from a pine floor that is a later feature of the old home.

A short paper, “Bermuda’s Cavendish Hall, Enslavement, and Historic Timber,” that is based on my knowledge of Cavendish and also on Csank’s dendrochronological findings, was awarded second place in the 2017 Andrew Hill Clark Award for papers at the PhD–level. The Historical Geography Specialty Group of the American Association of Geographers gives the award annually. A finding of this research is that Emancipation (and, therefore, the cessation of unpaid labour) may have impacted timber flows of the maritime Atlantic as well as the designs house builders and shipbuilders used in their construction projects.

Recently, I have expanded this piece and Csank plans to add his voice. The result will be a co-authored paper, “Mary Prince, Enslavement, Cavendish Hall, and Historic Timber,” which we plan to publish in Historical Geography. I add here that when I joined the team in 2014, I never thought it would result in a co-authored paper with a dendrochronologist! This is an example of what interdisciplinary work can bring about.

Q: What did you contribute to the team?

My knowledge of colonial slavery as it existed in Bermuda assisted the team. For example, I helped to locate primary source evidence showing that enslaved persons were part of the labour force that built Bermuda’s Royal Naval Dockyard.

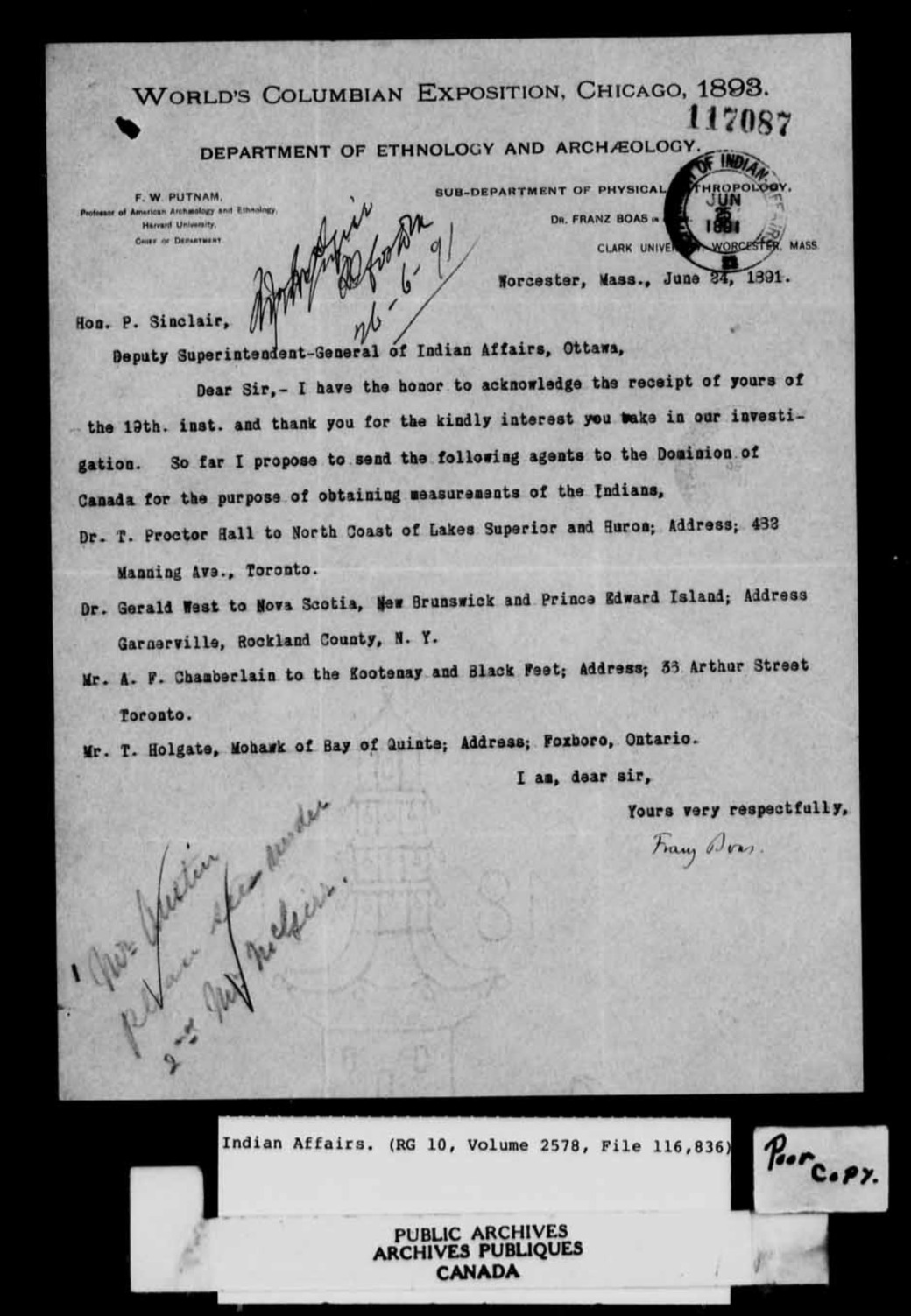

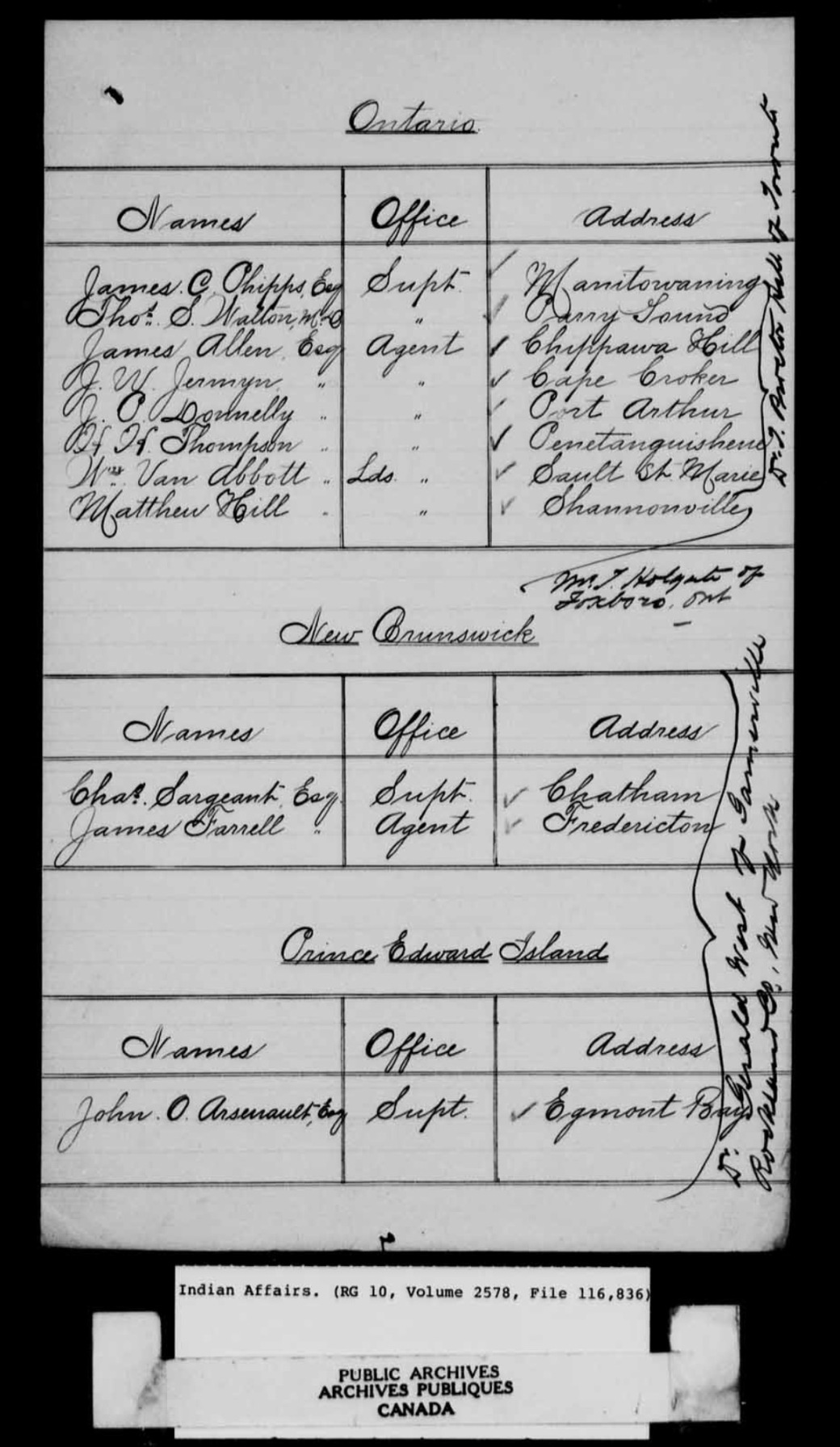

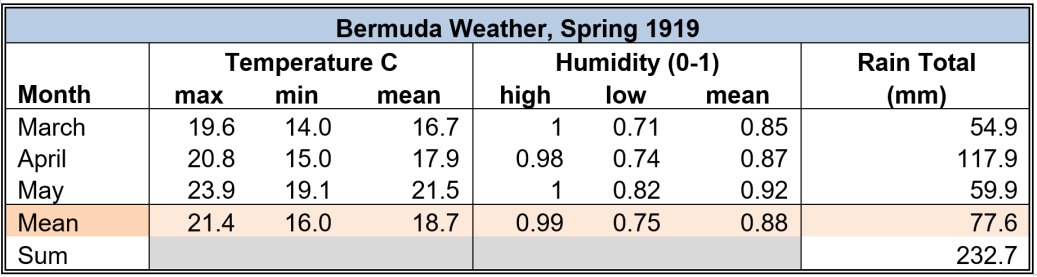

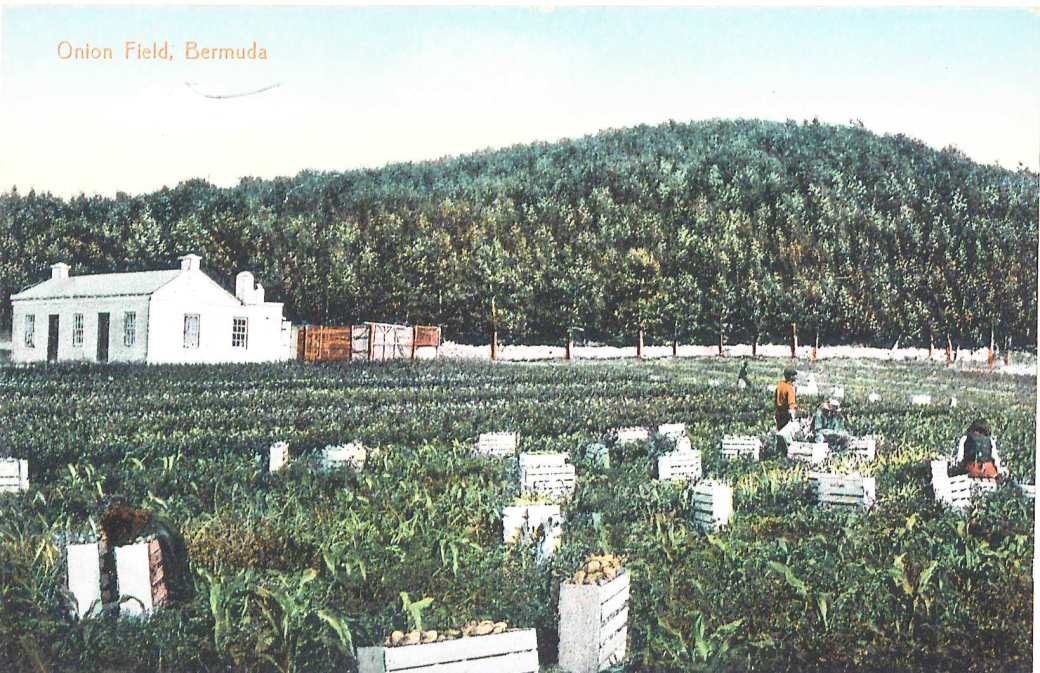

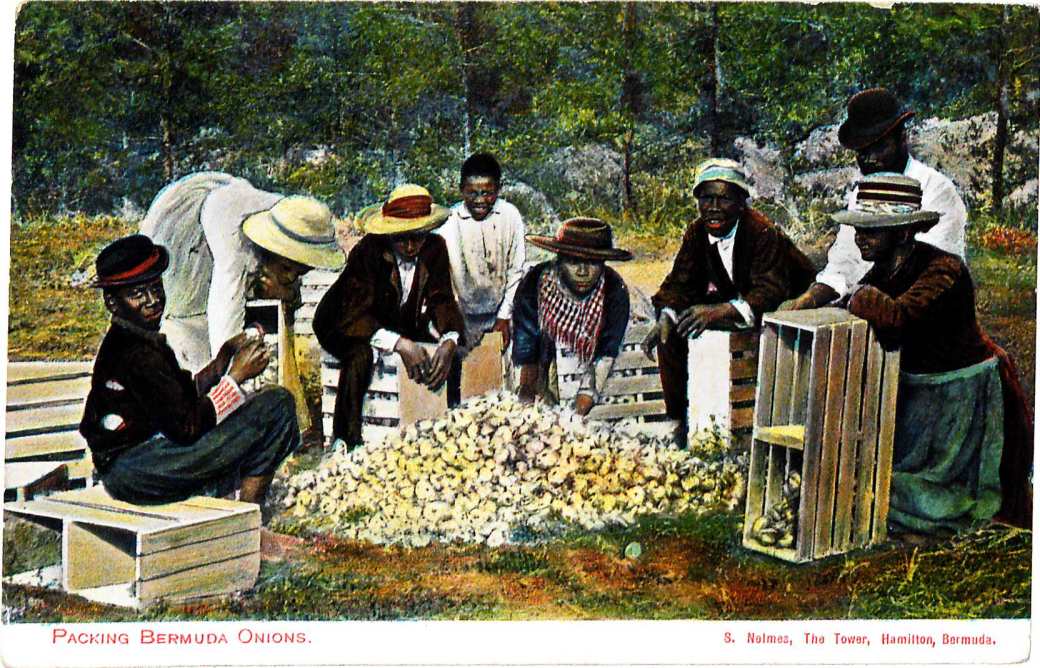

I also, however, have a literature background, and I believe that this, too, helped the team because it added to the team’s interdisciplinary nature. For example, my knowledge of Bermuda slave narratives augmented my thought about Bermuda’s agricultural past. An educated hunch put me on a jet bound for Bermuda last August (2017) where a visit to the Bermuda Archives to look at shipping manifests from the 1780s confirmed the existence of a large-scale pre-Emancipation onion plantation that has, until now, been overlooked. In 1781, for example, 658,500 pound of onions cleared Bermuda’s St. George’s and Hamilton ports combined. I’ve authored two short pieces about my preliminary findings regarding this onion plantation, one in Past Place (pages 9 & 10), and the other in MARITimes (see the bibliography following). This research keys to my postdoctoral work, which is focused on the Bermuda onion as a boundary object, but also looks at historic connections between Bermuda, the West Indies, and mainland American colonies.

Onion cultivation in Bermuda continued post-Emancipation right through to WWII when wartime interruptions, 1939-1945, followed by labour disputes with West Indian longshoremen in the early 1950s, brought an end to the trade. Texas-grown onions took over the market. No longer were Bermuda onions transported to West Indian or mainland markets. Even though Bermuda-grown onions were ready for market as a spring vegetable a few weeks earlier than Texas-grown onions, Bermudian onion growers were pushed out of the trade.

Figure 1: Onion Field, Bermuda (c. 1890), a postcard published by Wm. Weiss & Co.

Figure 2: Packing Bermuda Onions (c. 1890), a postcard published by Samuel Nelmes.

One finding that keys to Empire, Trees, and Climate is that pre-Emancipation, the Bermuda planters found an expanding market in the West Indies for their onions, and as their exports grew through the decades leading to Emancipation, so did the sizes of their ships. Possibly, this speaks to an increase in the flow of mainland timber to Bermuda for the purpose of shipbuilding.

Q: What did you hope to find out?

My chief hope was/is to find more information about enslavement in Bermuda, the West Indies, and mainland colonies as it pertains to timber. Enslaved workers harvested timber and worked as sawyers, carpenters, and house and shipbuilders. They also built furniture.

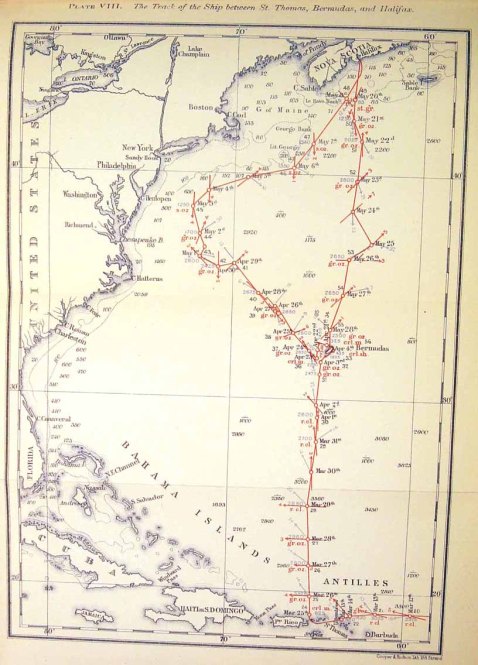

Shipping records located at the Bermuda Archives indicate an increase in the transportation of timber clearing Halifax for Bermuda after construction of Bermuda’s Royal Naval Dockyard began in 1795. This timber may have been from either Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. Records located at Charlottetown, also indicate timber transports from Prince Edward Island to Bermuda in this period. Therefore, one finding about enslavement in Bermuda is that enslaved people working in various wood-based industries in the territory were possibly working with timber originating in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island.

One thing I’ve learned is that when a researcher sets out to undertake research on any given subject, she or he often finds compelling information about a related subject that was not originally sought. This is why reflection is such an important component of research. A researcher must sit with the data that has been collected, be it archival, archaeological, dendrochronological, or some other type, and reflect on what it means. How does it fit into, or how does it not fit into, an existing narrative?

For example, Prince’s testimony, even as reduced as it was by the 1831 collaborative abolitionist storytelling, compiling, and editing team, spoke to me, albeit in a whisper, about the possibility of a Bermuda onion plantation. When I confirmed large-scale onion production by looking at shipping manifests located in the Bermuda Archives, I also learned that thousands of live ducks were shipped annually.

Yes, ducks! This finding has led to new research questions: What species of ducks were raised historically in Bermuda for shipping? Were the ducks raised solely for their flesh, or did they perform another function in Bermuda’s historical agricultural project? Where did the ducks originate? and How and when were the ducks transferred to Bermuda?

My hypothesis is that these were domesticated Muscovy ducks brought to Bermuda along with skilled enslaved Indigenous peoples from the Windward and Leeward Islands, and that the ducks were also used for pest control in the crops produced by enslaved labour. Additionally, duck dung may have helped to replenish soils exhausted from excessive nutrient uptake by exploitative agriculture, such as tobacco and sugar plantations. Both tobacco and sugar were tried as plantation crops in Bermuda soon after 1612 when settlement in Bermuda began.

Figure 3: Muscovy ducks. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Carl Sauer mentions briefly that the Muscovy duck was kept by island Carib people at the time of contact (The Early Spanish Main 59), and David Watts explains that prior to 1645 the Muscovy duck was incorporated into the mixed agricultural economy emerging in St. Kitts and Barbados (The West Indies 163). The English settled St. Kitts in 1623, and they settled Barbados four years later in 1627. Therefore, the time about which Watts writes is early days for both these two colonies. Watts adds that at this time, European settlers in St. Kitts and Barbados also made use of the Indigenous conuco method of agriculture common to both Carib and Arawak peoples, but whereas the Carib kept Muscovy ducks, the Arawak did not.

A conuco is a cultivation plot in which vegetable species that reproduce from cuttings are often planted in mounds. Starchy tubers such as sweet potatoes and manioc are the main components. Because these types of plants grow best in well-drained soil, the soil of a conuco was mounded when necessary. A conuco might be situated on any land suitable for growing, including sloped land, and between trees. Historically, when the soil of a conuco became depleted, it was left to rest for several years and another conuco was cultivated. Indigenous “kitchen” gardens as well as indigenous fruit trees augmented plant species grown in the conuco. My thought is that the Muscovy duck kept by the Carib people added to conuco and related Indigenous agriculture by way of pest control but also by duck dung, which helped to replenish the soil.

Bermuda was uninhabited by humans at the time the English settled the archipelago. Early settlers brought both black and Indigenous American people to the archipelago and enslaved them. Some of the enslaved Indigenous people brought to Bermuda may have come from English settlements such as St. Kitts and Barbados, or they may have been taken in raids on other islands. Some may have been Carib people who were familiar with the Muscovy duck. Food plants of Indigenous Americans were also imported. Sweet potato and arrowroot, both hailing from the Indigenous American food plant complex, were grown historically in Bermuda, for example. My thought is that the first generations of enslaved Indigenous cultivators in Bermuda may have practiced conuco agricultural methods, and kept kitchen gardens and indigenous fruit trees in Bermuda as they had on their home islands. They may also have kept Muscovy ducks.

It may also be that enslaved workers raised ducks, worked as “shepherds” to ducks, and also as caregivers to ducks aboard ships when the ducks were transported. They would have also constructed shipping crates for the live transport of the ducks. Because Bermudians had deforested their archipelago of Bermuda cedar for house building, shipbuilding, and for firewood by 1690, it may be that wood used to construct shipping crates in the 1700s was brought from mainland colonies. Once again, this keys to the flow of timber in the maritime Atlantic.

With the discovery of a pre-Emancipation onion plantation and the ducks, my hope to find out more about enslavement in Bermuda, the West Indies, and mainland colonies has taken the direction of a new and unforeseen historical story.

Q: What surprised you?

What can be more surprising than hundreds of thousands of pounds of onions being shipped annually from Bermuda, and thousands of ducks? Except that I haven’t been able to find a single mention of ducks in any secondary source about Bermuda.

In my mind, surprises are the best possible things that can happen when undertaking research. If you are able to receive surprises well, they may put your feet on a new path or enliven your thought process with a new idea.

Q: Why do you love your work?

What’s not to love about Bermuda? Especially when it’s January and you live in Canada?

I also love the interesting people I meet when I travel to do research. The Empire, Timber, Climate team members are terrific, but I also meet archivists, conservators, and other scholars, and they are great, too.

When I am in the field, reflecting on my findings, or maybe writing them up, time often slips by unnoticed. It’s peaceful, and I feel like I disappear into the historical story I am researching and telling. I love that feeling.

I also really love sharing my findings with interested others—by way of a history seminar, history class, public lecture, or a one-to-one discussion. My hope is to get my research out of the academy and shared with citizens young and old.

This brings my Research Profile to a close but also swings it back to my third specialization, the Pedagogy of Remembrance. By remembering and understanding The Middle Passage and colonial enslavement, people can better understand present social conditions—racism and its manifestations—that have arisen because of them.

The opening of historical consciousness means people may decide to work to repair existing relationships and to work for a more democratic future. This is what motivates me. I believe my research, and the sharing of my research, will help to make the world a better place.

I do this work for our children and grandchildren.

Bibliography

Darrell, Harriet, E. D., compiler. “Journal of John Harvey Darrell.” Bermuda Historical Quarterly. July-September, 1945, pp. 129-143.

Maddison-MacFadyen, Margôt. “Bermuda Onions.” Past Place: A newsletter of the Historical Geography Specialty Group of the American Association of Geographers. November 2017, pp. 9-10.

——. “Mary Prince and Bermuda Onions.” MARITimes, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2017, p. 23.

——. maryprince.org

——. “Reclaiming Histories of Enslavement in the Maritime Atlantic and a Curriculum: The History of Mary Prince” (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, 2017.

Prince, Mary. The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself. 1831. Rev. ed. Moira Ferguson, editor. Ann Arbor: U Michigan P. 1997, pp. 57-94.

Sauer, Carl O. The Early Spanish Main. Berkeley: U of California P, 1969.

Seixas, Peter. “A Model of Historical Thinking.” Educational Philosophy and Theory, 2015. pp. 1-13.

Seixas, Peter and Morton, Tom. The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts. Toronto: Nelson, 2013.

Simon, Roger I. A Pedagogy of Witnessing: Curatorial Practice and the Pursuit of Social Justice. New York: State U of New York, 2014.

Simon, Roger I., editor. The Touch of the Past: Remembrance, Learning, Ethics. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.

Watts, David. The West Indies: Patterns of Development, Culture and Environmental Change since 1492. New York: Cambridge U P, 1987.